We Visited the Rooftop of the Vietnam War’s Most Iconic Photo – You Won’t Believe How Little Has Changed

Gaining rare access to the rooftop that captured America’s most crushing moment in modern history

Contents:

The Fall of Saigon: Hubert Van Es’ Iconic Image

Operation Rooftop (our attempt at getting there!)

The Rooftop Now

How you Can Get There too!

The Fall of Saigon: Hubert Van Es’ Iconic Image

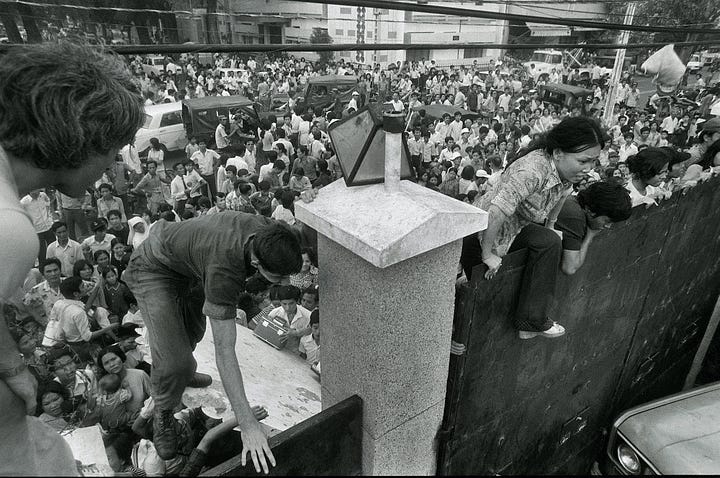

April 29th, 1975. The final act of the Vietnamese War was closing with grim urgency. Outside Saigon, The PAVN (People’s Army of North Vietnam) encircled with an army 300,000 strong, poised to invade. Unspoken panic permeated Saigon’s streets. Most of the fortunate had already fled; those who remained faced the full uncertainty of what was to come. The day before, South Vietnam’s President had resigned and hastily handed power to a reluctant General Dương Văn Minh. That same day, two South Vietnamese fighter pilots defected to the North, dropping six 250lb bombs on Tan Son Nhut Airbase, critically damaging South Vietnam’s last fighter jet air squadron. A rash of desertions spread across the remaining South Vietnamese army – 60,000, war-weary and often leaderless soldiers had drastically shrunk during April, by some accounts leaving the Saigon defence outnumbered 10:1.

Dutch photojournalist Hubert Van Es worked away in his makeshift darkroom in the Peninsula Hotel. It was the place that most international correspondents lived, flocking together as they seemingly often do in foreign appointments. He knew the evacuation was pending, but until the alarm bells rang, it was business as usual. Snap what he could.

“Van Es! Get out here! There’s a chopper on that roof!” Shouted Bert Okuley, United Press International correspondent, from their desk on the other side of the wall. He grabbed his camera and ran to the balcony.

On a rooftop, four blocks away, an American Bell UH-1 Huey helicopter was poised precariously. Below, stunned individuals – many American but some Vietnamese, frantically scrambled onto the rooftop and helped each other up a flimsy metal ladder, clambering towards salvation as the helicopter teetered above them.

From the radio in the background, Tennessee Ernie Ford’s ‘White Christmas’ played on the American Radio Service. It was an eerie, coded message for American nationals symbolising the beginning of Operation Frequent Wind – the last-resort airlift evacuation of Saigon. The song, designed to avoid widespread pandemonium in the streets, only added to the surrealism of the moment.

Van Es raised his camera, capturing the moment that would become an icon of America’s bitter end in Vietnam, a symbol of panic and loss—a surreal farewell to the war, caught between the chaos on the ground and fading hope in the sky.

The building, 22 Gia Long Street as it was named back then, was at the time occupied by the CIA and USAID offices. The individuals seen in the image are US employees and South Vietnamese persons of interest. However, in a classic example of misreporting, the Tokyo UPI desk edited the caption running in global newspapers to “A U.S. helicopter evacuating employees of the U.S. embassy”. Van Es spent years unsuccessfully attempting to have this doctored mistake changed. The lie has prevailed – with many, including me at one point, still thinking the photo shows the US Embassy.

It makes little sense, really; we have all seen equally iconic photos of the 1968 Viet Cong capture of the U.S. Embassy during the Tet Offensive. They are quite clearly different buildings. In fact, the US Embassy was evacuated earlier that morning in an even more hectic scene where over 12,500 people surged around the embassy hoping to be evacuated, bombarded by sporadic bursts of Viet Cong gunfire over the rooftops.

Van Es’ photo has held a strange grip on me for as long as I can remember. Even as a kid, my curiosity for modern history seemed insatiable, and I knew about the Vietnam War like back-of-my-hand.

Now, 25 years old, the inner child within me knew that I was going to get onto that rooftop no matter what.

Operation Rooftop - Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. 8/10/2024

It was a muggy day when our by-any-means plan sprang into action. Days of relentless monsoon rains had finally paused, leaving behind a heavy, damp heat as the sun cut through the lingering clouds with brutal intensity.

I’d walked past 22 Lý Tự Trọng on my first day in Ho Chi Minh City. I instantly recognised it. It was seemingly frozen in time. Yet, it remained entirely uncertain if it was possible to get onto the roof. That level of access was an unanswered question looming over our mission.

From the plaza garden in front of the Vincom Plaza shopping centre, we stood and recorded the intro to an upcoming video we are publishing about our journey to the rooftop and its profound history. The plaza is the only location offering a clear line of sight to the building, marked with a Hollywoodesque sign reading “LANDING ZONE”. There was evidence that you were once able to stand perpendicular to the rooftop at a good vantage point for photography, but with the construction of the mall it has now been obscured by the back stockrooms of shops.

Although the building was completely clear from the plaza, on Lý Tự Trọng Street, it camouflaged into a row of typical 1960s Vietnamese architecture—stacked into no-nonsense layers concrete, window, concrete, window. Perfectly nondescript for a former CIA outpost. We spent some time trying to figure out which building it was, walking up and down with no determined answer.

Eventually we resolved to ask local street vendors that were cooking various types of grilled skewers and stewing mighty pots of Bò Viên and Phở. I figured they probably knew the street quite well as they appeared to be the fixed-place kind of street vendors as per the collection of little plastic stools dotted around them.

With the famous heli photo in hand, the first woman I asked, in a rice farmer hat, was uncertain. The second vendor—a man laying aimlessly in a hammock—pointed to the glass-doored entrance of the building we were literally standing right in front of.

We stepped into a simple lobby of age-washed grey walls and white tiles. Quickly, I glanced around trying to figure out how we could slip up unnoticed to the rooftop incognito.

“Hello!” a voice boomed.

I looked to my left and saw a sharply dressed security guard in a crisp blue shirt and tie approaching us. This might be a bust.

Trying to keep cool, I showed him my phone and managed a slight shaky “hello… uh, we’re looking for how to get onto this rooftop?” UGH. Why did I make that a question? Am I unsure of myself? Get it together!

Expressionless, the calm way he dug into his shirt pocket to retrieve his glasses only put me on edge more. He glared down at my phone and sauntered over to his desk. He pulled open a drawer and lifted out a worn 200,000 Dong note. “200,000 Dong—per person,” he said, tapping the note, the price of entry: around £6.50 each. I clearly had nothing to worry about. I paid the man for us two.

“tầng chín” he said. I understood enough Vietnamese: floor 9.

The elevator rattled tiredly as it carried us up. I suddenly felt adrenaline rush though my veins. The doors were about to open to a place that had captured my fascination for years. I used to look at the photo as a child, one of history’s most significant moments, never thinking that one day I would be stood on the very rooftop where it happened. I felt my dreams run full circle.

Ding.

The Rooftop Now

Psst - we’re the new generation of travellers, dedicated to showcasing travel in a more thoughtful and meaningful way - through connections with people, unknown history, and local trends. It’s time we had an honest outlet for travel!

My first glimpse of the famous rooftop of Gia Long Street - and a quick clip of the former CIA offices.

The lift revealed a terrace of broken benches and garden lights running overhead. The bar which was once here in the 2000s remained as a chaotic mess. Its counter wrapped around the structure I had emerged from, strewn with bottles, some still holding a trace of liquor, others shattered on the floor. The counter’s façade, clad in corrugated iron, once painted blue, was now a rusty relic of what had been. Plant pots were dotted around, astonishingly all green and thriving despite their abandonment. It was as if nature was now overtaking the void of human presence.

The abandoned bar only amplified the sense of hurried departure that hovered over the place-an energy suspended in time, lingering like heavy, charged air before a storm.

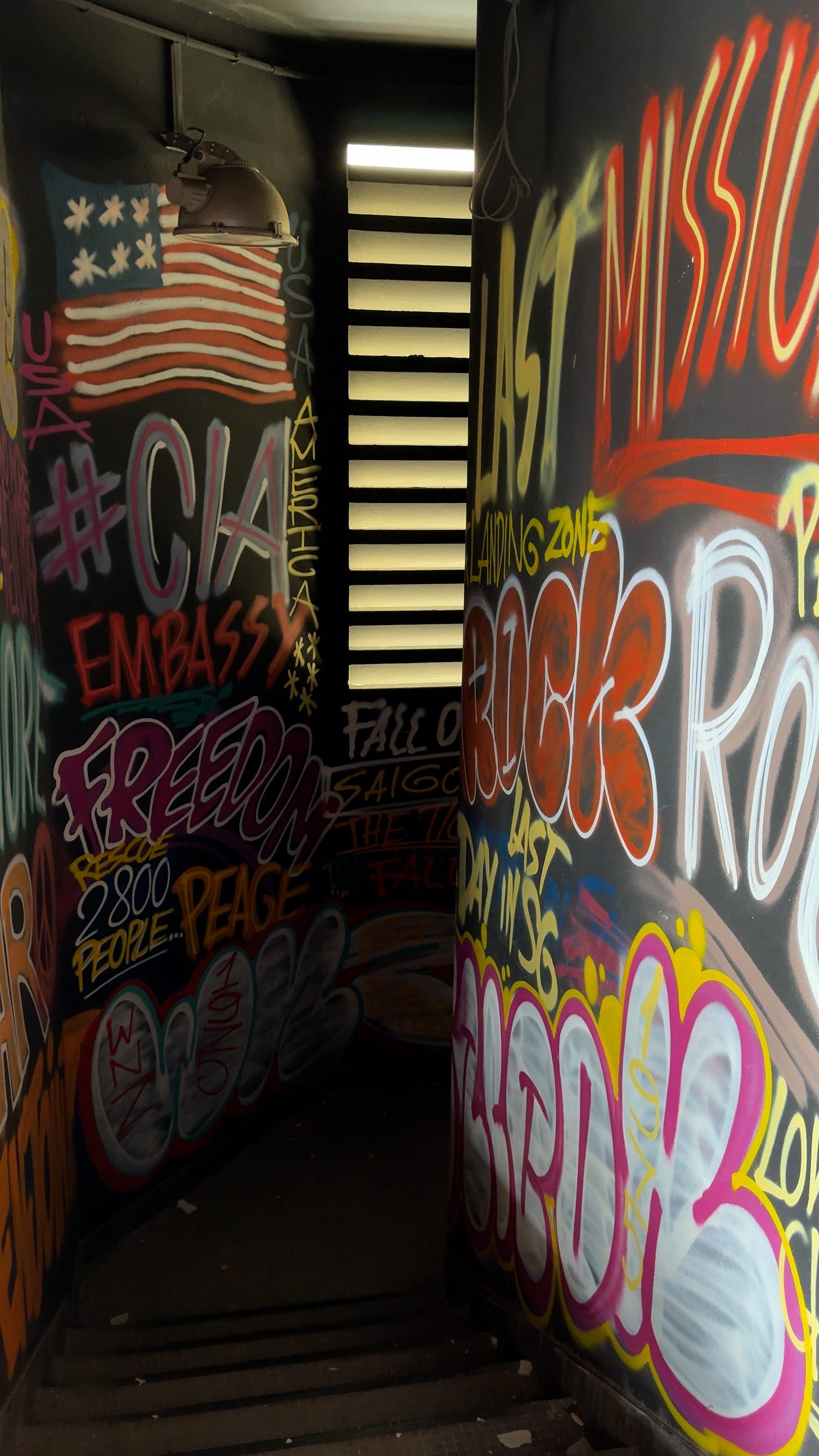

Behind the bar, a stairwell descended to the former CIA offices, its walls now graffitied with Vietnam War tropes: US soldiers, an American flag, the “Apocalypse Now” font, and, of course, a mighty Huey cutting through the air.

The terrace was part-covered by a roof – it was the mezzanine level where the evacuation happened. I walked purposefully across to the other side of the terrace so my first glimpse of it could be of the entire scene in all its glory. Every step heightened my anticipation in the knowledge that one of the most special moments of my life about to unfold in front of my eyes.

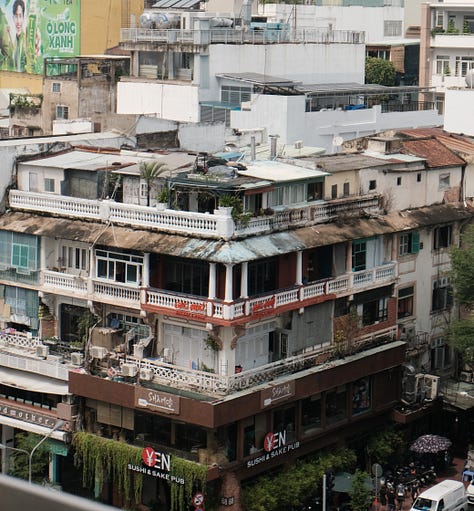

I turned. There it was. A remarkable time capsule of a changing world stood in quiet stoicism. The maintenance structure that the Huey had landed on appeared untouched, as if it had defied time. Nothing had been painted over since. Sure, some details were different: three telephone communication pillars now flanked the mezzanine corners, floodlights had been added, and the ladder, which I’d learned wasn’t the original from the iconic photograph, now stood on a different side.

But none of that mattered. On that rooftop, it felt like I had stumbled into the day after the helicopter took off—the bar’s broken bottles and scattered mess an echo of the chaos that must have defined the Fall of Saigon. I could see the chaos those evacuees must have felt having to leave everything behind in an instant. Some, CIA officials, never officially in South Vietnam – and now I followed in their clandestine footsteps. I couldn’t resist descending the stairwell to briefly poke my head into the former CIA office, now seemingly an insurance company. I didn’t want to be caught so I walked into the office corridor and crouched underneath the windows of their offices, took a couple rapid photos and ducked out.

On the upper mezzanine level (aka the landing sight), a strange mix of mechanical machinery had been forgotten on the roof, now engulfed in rust. These vintage-looking contraptions seemed like they had been here since 1975. Broken slabs of concrete were piled along the wall edges, frayed wiring poking out of them. This level had been completely frozen in time.

Yet, beyond the terrace, the view had changed immensely. Across the street was the offices of the Vincom building, a glass-clad, modern highrise. Older hotels from the 80s dotted the area. In the distance, a barrage of futurist corporate high-rises now dominated the skyline from the Bitexco Financial Tower to Landmark 81, eclipsing even Malaysia’s Petronas Towers in height.

But those high-rises were just distant silhouettes—mere whispers of Vietnam's incredible post-war rebirth, removed from where I now stood like a bubble sealed off in time. Immediately around me I still saw the backs of Vietnam’s 20th century “vertical villages” that characterised 60s Saigon. Laundry hung around mesh-framed external corridors, covered in corrugated, rusting iron roofs. Grime ran down the sides of the buildings and concrete water towers. On nearby rooftops, plants were scattered among chromium water cisterns. Below, in apartment courtyards, school children in uniforms nearly identical to those of five decades past played, unaware of the history enveloping them.

I felt the heaviness of 1975 all around me. The rooftop of 22 Lý Tự Trọng, unassuming and raw, was a monument of the death of one nation and the birth of another.

Reaching into my backpack, I pulled out my father’s trusty old film—a 1972 Olympus OM-1. It was a choice favourite for photojournalists reporting in the field at the time. It felt poetic.

Mouth agape, I slowly wound the lever, and raised the camera to my eye.

*click*

How you Can also Get onto The Rooftop

For more alternative and unique recommendations, follow our Instagram and TikTok! We post daily.

Technically, you shouldn’t be allowed onto the rooftop. However, we found no issue getting up there. Here’s a brief of how we did it:

First, locate the building, which does blend into the street a bit. The address is 22 Lý Tự Trọng Street (the name of the road was changed following the end of the War). If you stand from the plaza in front of the Vincom shopping centre, you’ll be able to see the rooftop marked with a sign that says “LANDING ZONE”.

Now, go to the building’s lobby. It is left of an arched sideroad which will have some street food stands in it. You will see a small lobby with an elevator.

Ask the security guard if you can go up. The guard didn’t speak English, but we showed him the famous photo, and he was very friendly. He will ask for some money, for us it was 200,000VND per person, a fair price to pay considering he might be putting himself on the line to allow you to do this.

In the lift, go to the top floor. There it will open onto the rooftop at an abandoned bar. When entering the rooftop, you will see a set of steps and a ladder up to the mezzanine where the photo was taken.

SOURCES

Coontz, L. 2021. ‘The real story behind the iconic ‘fall of Saigon’ photo. Coffee or Die Magazine: https://coffeeordie.com/iconic-fall-of-saigon-photo#:~:text=Air%20America%20pilots%20land%20on,Es%2C%20April%2029%2C%201975.

Engelmann, Larry. 1990. Tears before the Rain: An Oral History of the Fall of South Vietnam.

Es, Hubert van. 2009. ‘Thirty years at 300 millimeters’. The New York Times.

This is hard to believe the history behind the building. I remembered the devastating loss of life.